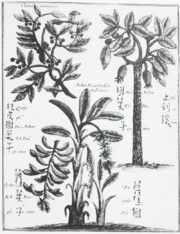

Cinnamomum aromaticum

| Cassia | |

|---|---|

|

|

| from Koehler's Medicinal-Plants (1887) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Laurales |

| Family: | Lauraceae |

| Genus: | Cinnamomum |

| Species: | C. aromaticum |

| Binomial name | |

| Cinnamomum aromaticum Nees |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Cinnamomum cassia Nees ex Blume |

|

Cinnamomum aromaticum, called cassia or Chinese cinnamon, is an evergreen tree native to southern China, Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam. Like its close relative Cinnamomum verum, also known as "Ceylon cinnamon",[1] it is used primarily for its aromatic bark, which is used as a spice. In the United States of America, cassia is often sold under the culinary name of "cinnamon", a practice banned in many other countries. The buds are also used as a spice, especially in India, and were once used by the ancient Romans.

The tree grows to 10–15 m tall, with greyish bark and hard elongated leaves that are 10–15 cm long and have a decidedly reddish colour when young.

Contents |

Production and uses

Cinnamomum aromaticum is a close relative to Ceylon cinnamon (C. verum), Saigon cinnamon (C. loureiroi, also known as "Vietnamese cinnamon"), camphor laurel (C. camphora), malabathrum (C. tamala), and Indonesian cinnamon (C. burmannii). As with these species, the dried bark of cassia is used as a spice. Cassia cinnamon's flavour is less delicate than that of Ceylon cinnamon; for this reason, the less expensive cassia is sometimes called "bastard cinnamon".[2]

Whole branches and small trees are harvested for cassia bark, unlike the small shoots used in the production of cinnamon; this gives cassia bark a much thicker and rougher texture than that of true cinnamon.

Most of the spice sold as cinnamon in the United States and Canada (where Ceylon cinnamon is still generally unknown) is actually cassia. In some cases, cassia is labeled "Chinese cinnamon" to distinguish it from the more expensive Ceylon cinnamon (C. verum), which is the preferred form of the spice used in Mexico, Europe and Oceania.[3] "Indonesian cinnamon" can also refer to C. burmannii, which is also commonly sold in the United States, labeled only as cinnamon.

Cinnamomum aromaticum is produced in both China and Vietnam. Until the 1960s, Vietnam was the world's most important producer of Saigon cinnamon (C. loureiroi), a species which has a higher oil content than cassia, and consequently has a stronger flavor. Saigon cinnamon is so closely related to cassia that it was often marketed as cassia (or, in North America, "cinnamon"). Of the three forms of cassia, it is the form which commands the highest price. Because of the disruption caused by the Vietnam War, however, production of C. burmannii, in the highlands of the Indonesia on island of Sumatra, was increased to meet demand, and Indonesia remains one of the main exporters of cassia today. Indonesian cassia has the lowest oil content of the three types of cassia and, consequently, commands the lowest price. Saigon cinnamon, only having become available again in the United States since the early 21st century, has an intense flavour and aroma and a higher percentage of essential oils than Indonesian cassia. Cassia has a stronger and sweeter flavor, similar to Saigon cinnamon, although the oil content is lower. In China (where it is produced primarily in the southern provinces of Guangxi, Guangdong, and Yunnan) cassia is known as tung hing.[4]

Cassia bark (both powdered and in whole, or "stick" form) is used as a flavouring agent for confectionary, desserts, pastries, and meat; it is specified in many curry recipes, where Ceylon cinnamon is less suitable. Cassia is sometimes added to Ceylon cinnamon, but is a much thicker, coarser product. Cassia is sold as pieces of bark (as pictured below) or as neat quills or sticks. Cassia sticks can be distinguished from Ceylon cinnamon sticks in the following manner: cinnamon sticks have many thin layers and can easily be made into powder using a coffee or spice grinder, whereas cassia sticks are extremely hard, are usually made up of one thick layer, and can break an electric spice or coffee grinder if one attempts to grind them without first breaking them into very small pieces.

Cassia buds, although rare, are also occasionally used as a spice. They resemble cloves in appearance and have a mild, flowery cinnamon flavor. Cassia buds are primarily used in old-fashioned pickling recipes, marinades, and teas.[5][6]

Health benefits and risks

Cassia (called ròu gùi; 肉桂 in Chinese) is used in traditional Chinese medicine, where it is considered one of the 50 fundamental herbs.[7]

In 2006, a study reported no statistically significant additional benefit when cinnamon cassia powder was given to type 2 diabetes patients who were already being treated with metformin.[8] A systematic review of research indicates that cinnamon may reduce fasting blood sugar, but does not have an effect on hemoglobin A1C, a biological marker of long-term diabetes.[9]

Chemist Richard Anderson says that his research has shown that most, if not all, of cinnamon's antidiabetic effect is in its water-soluble fraction, not the oil (the ground cinnamon spice itself should be ingested for benefit, not the oil or a water extraction). In fact, some cinnamon oil-entrained compounds could prove toxic in high concentrations. Cassia's effects on enhancing insulin sensitivity appear to be mediated by polyphenols.[10] Despite these findings, cassia should not be used in place of anti-diabetic drugs, unless blood glucose levels are closely monitored, and its use is combined with a strictly controlled diet and exercise program.

Due to a toxic component called coumarin, European health agencies have warned against consuming high amounts of cassia.[11]

Other possible toxins founds in the bark/powder are cinnamaldehyde and styrene[12].

History

In classical times, four types of cinnamon were distinguished (and often confused):

- Cassia (Hebrew qəṣi`â), the bark of Cinnamomum iners from Arabia and Ethiopia

- True Cinnamon (Hebrew qinnamon), the bark of Cinnamomum zeylanicum from Sri Lanka

- Malabathrum or Malobathrum (from Sanskrit तमालपत्रम्, tamālapattram, literally "dark-tree leaves"), Cinnamomum malabathrum from the north of India

- Serichatum, Cinnamomum aromaticum from Seres, that is, China.

In Exodus 30:23-4, Moses is ordered to use both sweet cinnamon (Kinnamon) and cassia (qəṣî`â) together with myrrh, sweet calamus (qənê-bosem, literally cane of fragrance, could also be a mistranslation of cannabis[13]) and olive oil to produce a holy oil to anoint the Ark of the Covenant. Psalm 45:8 mentions the garments of the king (or of Torah scholars) that smell of myrrh, aloes and cassia.

An early reference to the trade of cinnamon occurs around 100 BC in Chinese literature. After the explorer Zhang Qian's return to China, the Han Dynasty pushed the Xiongnu back, and trade and cultural exchange flourished along the Northern Silk Road. Goods moving by caravan to the west included gold, rubies, jade, textiles, coral, ivory and art works. In the opposite direction moved bronze weapons, furs, ceramics and cinnamon bark.[14] The first Greek reference to kasia is found in a poem by Sappho in the 7th century B.C.

According to Herodotus, both cinnamon and cassia grow in Arabia, together with incense, myrrh, and ladanum, and are guarded by winged serpents. The phoenix builds its nest from cinnamon and cassia. But Herodotus mentions other writers that see the home of Dionysos, e.g., India, as the source of cassia. While Theophrastus gives a rather good account of the plants, a curious method for harvesting (worms eat away the wood and leave the bark behind), Dioscorides seems to confuse the plant with some kind of water-lily.

Pliny (nat. 12, 86-87) gives a fascinating account of the early spice trade across the Red Sea in "rafts without sails or oars", obviously using the trade winds, that costs Rome 100 million sesterces each year. According to Pliny, a pound (the Roman pound, 327 g) of cassia, cinnamon, or serichatum cost up to 300 denars, the wage of ten months' labour. Diocletian's Edict on Maximum Prices[15] from 301 AD gives a price of 125 denars for a pound of cassia, while an agricultural labourer earned 25 denars per day.

The Greeks used kásia or malabathron to flavour wine, together with absinth wormwood (Artemisia absinthia). Pliny mentions cassia as a flavouring agent for wine as well[16] Malabathrum leaves (folia) were used in cooking and for distilling an oil used in a caraway-sauce for oysters by the Roman gourmet Gaius Gavius Apicius.[17] Malabathrum is among the spices that, according to Apicius, any good kitchen should contain.

Egyptian recipes for kyphi, an aromatic used for burning, included cinnamon and cassia from Hellenistic times onwards. The gifts of Hellenistic rulers to temples sometimes included cassia and cinnamon as well as incense, myrrh, and Indian incense (kostos), so we can conclude that the Greeks used it in this way too.

The famous Commagenum, an unguent produced in Commagene in present-day eastern Turkey, was made from goose-fat and aromatised with cinnamon oil and spikenard (Nardostachys jatamansi). Malobrathum from Egypt (Dioscorides I, 63) was based on cattle-fat and contained cinnamon as well; one pound cost 300 denars. The Roman poet Martial (VI, 55) makes fun of Romans who drip unguents, smell of cassia and cinnamon taken from a bird's nest, and look down on him who does not smell at all.

Cinnamon, as a warm and dry substance, was believed by doctors in ancient times to cure snakebites, freckles, the common cold, and kidney troubles, among other ailments.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Cinnamomum verum information from NPGS/GRIN". www.ars-grin.gov. http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?70183. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ↑ Google Books search

- ↑ Needs cite web

- ↑ needs cite web

- ↑ needs cite web

- ↑ photo needs cite web

- ↑ Wong, Ming (1976). La Médecine chinoise par les plantes. Le Corps a Vivre series. Éditions Tchou.

- ↑ Suppapitiporn S, Kanpaksi N, Suppapitiporn S (September 2006). "The effect of cinnamon cassia powder in type 2 diabetes mellitus". Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 89 Suppl 3: S200–5. PMID 17718288.

- ↑ Dugoua JJ, Seely D, Perri D, et al. (September 2007). "From type 2 diabetes to antioxidant activity: a systematic review of the safety and efficacy of common and cassia cinnamon bark". Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 85 (9): 837–47. doi:10.1139/y07-080. PMID 18066129.

- ↑ Polyphenols from Cinnamon increase insulin sensivity: functional and clinical aspects 4th International Congress Dietary Antioxidants and trace elements Monastir, Tunisia, April 2005

- ↑ NPR: German Christmas Cookies Pose Health Danger

- ↑ High daily intakes of cinnamon: Health risk cannot be ruled out. BfR Health Assessment No. 044/2006, 18 August 2006 15p

- ↑ Reinhard K. Sprenger (2004). Campus Verlag. ed. Die Entscheidung liegt bei dir!: Wege aus der alltäglichen Unzufriedenheit. Campus Verlag. ISBN 359337442. http://books.google.com/?id=CBXxnaGk0hwC&pg=PA40&dq=Exodus+30:23+cannabis.

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan,Silk Road, North China, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham

- ↑ E.R. Graser (1940) A text and translation of the Edict of Diocletian Editor: T. Frank in An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome Volume V: Rome and Italy of the Empire, first ed., Publisher: Johns Hopkins Press

- ↑ Pliny, nat. 14, 107f.

- ↑ De re coquinaria, I, 29, 30; IX, 7

General references

- Dalby, Andrew (1996). Siren Feasts: A History of Food and Gastronomy in Greece. London: Routledge.

- Faure, Paul (1987). Parfums et aromates de l'antiquité. Paris: Fayard.

- Paszthoty, Emmerich (1992). Salben, Schminken und Parfüme im Altertum. Mainz, Germany: Zabern.

- Paterson, Wilma (1990). A Fountain of Gardens: Plants and Herbs from the Bible. Edinburgh.

External links

- Complementary and Alternative Healing University (Chinese Herbology)

- List of Chemicals in Cassia (Dr. Duke's Databases)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||